Roman Catholic Church

Introduction

The Roman Catholic Church has developed a significant body of teaching on Interreligious Dialogue. Admittedly, over the centuries the attitude of Catholics towards believers from other religions has generally been very negative. It is summed up in the Latin dictum, extra ecclesiam nulla salus (outside the church, no salvation). This phrase was originally used by the Fathers to refer to Christians in danger of separating from the church by heresy or schism, but was later used indiscriminately against Jews, Muslims, believers in other religions and even against fellow Christians. Happily, the atmosphere is now completely different.

Pope John XXIII initiated the change. He called the Second Vatican Council to update the Church’s relation with the world and all its peoples. Having been challenged by the French Jewish scholar, Jules Isaac, on the role that Christian anti-Semitism played in the suffering of the Jews down through the ages, culminating in the Shoah, he directed the Council to change the Church’s attitude towards the Jews.

His successor, Pope Paul VI, continued the task. His programmatic encyclical, Ecclesiam Suam: Paths of the Church, envisioned the church in dialogue with the entire world, with believers in God, with other Christians and with other Catholics. This vision influenced the Council and is the first time that the word “dialogue” appears in the Church’s teaching.

To implement the Council’s teaching on relations with believers from other religions, Pope Paul VI set up the Secretariat for Non-Christians. This was renamed the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue (PCID) by Pope John Paul II in 1998. This department has engaged with individuals and organizations from other religions, sent delegations to other countries, received delegations at the Vatican and provided formation and teaching in the light of their and other’s lived experience of interreligious dialogue. Their important teaching documents are listed in chronological order in the adjacent sub-menu.

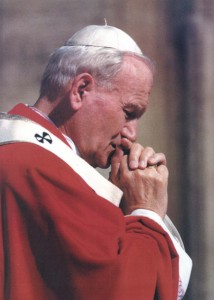

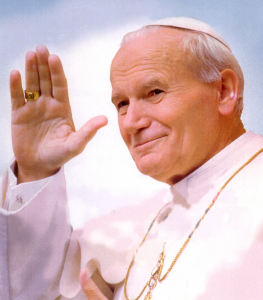

Pope John Paul II, during his 25-year papacy, through his encyclicals, audiences, speeches, addresses to guests and meetings with religious leaders during his pastoral visits to other countries, contributed much to the teaching and practice of interreligious dialogue. Prayer for Peace in Assisi, and again in 1993 and in 2001. We provide some of the significant documents of his teaching in the adjacent sub-menu and in the menu on Jewish-Christian Relations. Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis have continued these practices and made their own distinctive contributions to the practice and theory of interreligious dialogue. Catholic Dioceses throughout the world were encouraged to take up this new challenge of interreligious dialogue.

Many of them set up Commissions to oversee the interreligious apostolate, often in tandem with the ecumenical apostolate. The Commissions promote the church’s teaching on interreligious dialogue and form people to build relations with the religious leaders and people in their area. Often the Conference of Bishops and Federation of Bishops Conferences have set up agencies to share resources, ideas and formation on interreligious dialogue. Please find below links to some of the Catholic national and federal interreligious bodies.

RC Teaching Documents

1964, Paul VI, Ecclesiam Suam: Paths of the Church

In this encyclical Pope Paul VI introduces the word “dialogue” into the magisterial teaching of the Catholic Church. He presents a sweeping vision of four concentric circles (n. 96):

- the entire world (nn. 97-106);

- religious believers (nn. 107 – 108);

- Christians from the various churches (nn. 109 – 112);

- the members of the Catholic Church (nn. 113 – 118).

Vatican II used the same schema (in reverse order) in Lumen Gentium 14 – 16 and also in Gaudium et Spes n. 92. And here is the crucial point – each of these circles is an arena for dialogue. The word “dialogue” appears 80 times in the encyclical, over half of which is devoted to the theme of dialogue in its origins, mode, manner and addressees.

http://w2.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_06081964_ecclesiam.html

Available as PDF: Paul VI, 1964, “Ecclesiam Suam: Paths of the Church”

Español: http://w2.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/es/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-vi_enc_06081964_ecclesiam.html

Korean/ 한국말: http://www.cbck.or.kr/book/book_list5.asp?p_code=k5150&seq=400201&page=8&KPope=%B9%D9%BF%C0%B7%CE6%BC%BC&KBunryu=&key=Title&kword=

1965, Vatican II, Dignitatis Humanae: Declaration on Religious Liberty

“Christendom” was the merging of state and religious authority which established the church for much of its history, enabling it to promote its doctrines and morals through law and sometimes even by force. Dignitatis Humanae, with its assertion of freedom of conscience and the separation of church and state, marks a radical departure from the imperial mode to one in accord with the Gospel and based on respect for the dignity of the human person.

Available as a PDF here: Dignitatis Humanae: Declaration on Religious Liberty

Korean/ 한국말: http://www.cbck.or.kr/book/book_list.asp?p_code=k5140&seq=401949&page=1&key=Title&kword=Dignitatis%20Humanae

1965, Vatican II, Nostra Aetate: Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions

As Vatican II was a turning point in the church’s approach to the modern world, Nostra Aetate is the Council document that expresses that change in relation to other religions. It is a truly “revolutionary” document:

- It was the first time that the Church spoke positively about other religions.

- It has significant treatment of Islam, with implicit references to themes from Muslim spirituality and practice.

- It reversed the traditional “teaching of contempt” regarding the Jews and refuted the ancient charge of deicide.

- It is the official expression—at the highest level of Church teaching, an ecumenical council with nearly all of the bishops of the Church—of a radical change in the Church’s teaching and attitudes towards other religions.

Recent popes have called Nostra Aetate “the Magna Carta” of the Church’s teaching on other religions (John Paul II, 1999; Benedict XVI, 2005). It is the turning point on which the Church transformed its outlook and attitude towards believers from other religions.

“Nostra Aetate: Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions.” In Vatican Council II: The Basic Sixteen Documents. A Completely Revised Translation in Inclusive Language, edited by Austin Flannery OP, 569-74. Northport, NY; Dublin, Ireland: Costello Publishing Company; Dominican Publications, 1996.

Korean/ 한국말: http://www.cbck.or.kr/book/book_list.asp?p_code=k5140&seq=401950&page=1&key=Title&kword=Nostra%20Aetate#

Supplementary Resource Materials

Pope Francis, Interreligious General Audience, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Conciliar Declaration “Nostra Aetate“, St Peter’s Square, Wednesday, 28 October 2015.

Rabbinat Council of America; Conference of European Rabbis; Chief Rabbinate of Israel. “Between Jerusalem & Rome: Reflections of 50 Years of Nostra Aetate.” (2017): 21. Published electronically 31 August 2017. http://cjcuc.org/2017/08/31/between-jerusalem-and-rome/.

Polish, Daniel F. “Nostra Aetate: A Lever that Moved the World.” America Press Inc, http://americamagazine.org/issue/nostra-aetate-lever-moved-world.

On Tuesday, 12 January 2016, Rabbi Daniel Polish delivered this year’s John Courtney Murray, S.J., lecture at Fordham University, New York, NY. In the lecture “Nostra Aetate: A Lever That Moved the World,” Rabbi Daniel Polish discussed the progress made in ecumenical and interfaith relations in the 50 years since Nostra Aetate.

Australian Catholic Bishops Conference: Nostra Aetate: 50th Anniversary Reflections, 2015

A document published in 2015 to mark the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the publication of Nostra Aetate. It was prepared by the Bishops Commission for Ecumenism and Inter-religious Relations.

Nostra Aetate: The Leaven of Good – Part III / Interreligious Dialogue Today and the Demands of the Future

The final part in a 3-part series of films commemorating the 50th Anniversary celebration of the document “Nostra aetate”, the Catholic Church’s declaration on interreligious outreach. This part looks at interreligious dialogue today, the situations and relationships which call for dialogue among followers of religions. https://vimeo.com/145252146

Clips of interviews from the film are available in the Nostra Aetate Video Archive on the DigitalGeorgetown website: https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1043689

Fitzgerald, Michael, Nostra Aetate: A Guide for Ongoing Dialogue

A paper presented in Rome, 3 October 2015, at the request of the USG/UISG Commission for Interreligious Dialogue

For an account of the origins of Nostra Aetate and its passage through the Council see Stransky, Thomas. “The Genesis of Nostra Aetate“. (24 October) America Press Inc, 2005 [cited 1 June 2010]. Available from http://www.americamagazine.org/content/article.cfm?article_id=4431.

Madigan, Daniel A. “Nostra Aetate and the Questions It Chose to Leave Open.” Gregorianum 87, no. 4 (2006): 781-95.

McInerney, Patrick J. “Nostra Aetate: The Catholic Church’s Journey into Dialogue.” The Australasian Catholic Record 90, no. 3 (2013): 259-71.

Published with permission of ACR, 2015.

Kessler, Edward. “Nostra Aetatate – 50 Years On“. The Tablet, 2012

1962 – 1965 Vatican II

While Nostra Aetate is the Vatican II declaration on the Church’s relation to other religions, the other documents of the Council provide the context for its revolutionary teaching as well as ecclesiological and missiological backing.

While Nostra Aetate is the Vatican II declaration on the Church’s relation to other religions, the other documents of the Council provide the context for its revolutionary teaching as well as ecclesiological and missiological backing.

Vatican II. “Lumen Gentium: Dogmatic Constitution on the Church.”

Korean/ 한국말: http://www.cbck.or.kr/book/book_list.asp?p_code=k5140&seq=401963&page=1&key=Title&kword=Lumen%20Gentium#

Vatican II. “Ad Gentes Divinitus: Decree on the Church’s Missionary Activity.”

Korean/ 한국말: http://www.cbck.or.kr/book/book_list.asp?p_code=k5140&seq=401953&page=1&key=Title&kword=Ad%20Gentes%20Divinitus

Vatican II. “Gaudium Et Spes: Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World.”

Korean/ 한국말: http://www.cbck.or.kr/book/book_list.asp?p_code=k5140&seq=401961&page=1&key=Title&kword=Gaudium%20Et%20Spes:

For a selection of quotes in English from these Vatican II documents on the Church’s self-understanding of her identity and role in regard to other religions and interreligious dialogue see Vatican II on Religions & Dialogue.

1975, Paul VI, Evangelii Nuntiandi

Evangelii Nuntiandi: On Evangelisation in the Modern World, is Pope Paul VI’s Apostolic Exhortation published in December 1975. The previous year’s Synod of Bishops had explored the theme of evangelisation in the light of the Second Vatican Council. Unable to agree on a final statement, the Synod Fathers handed all their deliberations over to the Pope. The resulting document is a profound and inspiring reflection on evangelisation.

Evangelii Nuntiandi: On Evangelisation in the Modern World, is Pope Paul VI’s Apostolic Exhortation published in December 1975. The previous year’s Synod of Bishops had explored the theme of evangelisation in the light of the Second Vatican Council. Unable to agree on a final statement, the Synod Fathers handed all their deliberations over to the Pope. The resulting document is a profound and inspiring reflection on evangelisation.

Introduction (1-5)

I. From Christ the Evangelizer to the Evangelizing Church (6-16)

II. What is Evangelization? (17-24)

III. The Content of Evangelization (25-39)

IV. The Methods of Evangelization (40-48)

V. The Beneficiaries of Evangelization (49-58)

VI. The Workers for Evangelization (59-73)

VII. The Spirit of Evangelization (74-80)

Conclusion (81-82)

Given that Pope Paul had introduced the word “dialogue” to the Church over a decade earlier in his programmatic encyclical, Ecclesiam Suam and in his world-wide travels had shown genuine pastoral leadership and sensitivity in meetings with believers from other religions, it is surprising that there is no mention of interreligious dialogue in Evangelii Nuntiandi. We do find the classical “fulfillment approach” to other religions, as shown in paragraph 53 quoted below. It is not until Pope John Paul’s Redemptoris Missio in 1990 that interreligious dialogue will be affirmed as “a part of the Church’s evangelizing mission” (RM, #55).

Vatican Website: http://w2.vatican.va/content/paul-vi/en/apost_exhortations/documents/hf_p-vi_exh_19751208_evangelii-nuntiandi.html

Korean/한국말 : http://www.cbck.or.kr/book/book_search.asp?p_code=k5110&seq=401534&page=1&Cat=A&key=Title&kword=evangelii%20nuntiandi

53. This first proclamation is also addressed to the immense sections of mankind who practice non-Christian religions. The Church respects and esteems these non Christian religions because they are the living expression of the soul of vast groups of people. They carry within them the echo of thousands of years of searching for God, a quest which is incomplete but often made with great sincerity and righteousness of heart. They possess an impressive patrimony of deeply religious texts. They have taught generations of people how to pray. They are all impregnated with innumerable “seeds of the Word” and can constitute a true “preparation for the Gospel,” to quote a felicitous term used by the Second Vatican Council and borrowed from Eusebius of Caesarea.

Such a situation certainly raises complex and delicate questions that must be studied in the light of Christian Tradition and the Church’s magisterium, in order to offer to the missionaries of today and of tomorrow new horizons in their contacts with non-Christian religions. We wish to point out, above all today, that neither respect and esteem for these religions nor the complexity of the questions raised is an invitation to the Church to withhold from these non-Christians the proclamation of Jesus Christ. On the contrary the Church holds that these multitudes have the right to know the riches of the mystery of Christ – riches in which we believe that the whole of humanity can find, in unsuspected fullness, everything that it is gropingly searching for concerning God, man and his destiny, life and death, and truth. Even in the face of natural religious expressions most worthy of esteem, the Church finds support in the fact that the religion of Jesus, which she proclaims through evangelization, objectively places man in relation with the plan of God, with His living presence and with His action; she thus causes an encounter with the mystery of divine paternity that bends over towards humanity. In other words, our religion effectively establishes with God an authentic and living relationship which the other religions do not succeed in doing, even though they have, as it were, their arms stretched out towards heaven.

This is why the Church keeps her missionary spirit alive, and even wishes to intensify it in the moment of history in which we are living. She feels responsible before entire peoples. She has no rest so long as she has not done her best to proclaim the Good News of Jesus the Savior. She is always preparing new generations of apostles. Let us state this fact with joy at a time when there are not lacking those who think and even say that ardor and the apostolic spirit are exhausted, and that the time of the missions is now past. The Synod has replied that the missionary proclamation never ceases and that the Church will always be striving for the fulfillment of this proclamation. (EN, 53)

1984, Secretariate for Non-Christians, Dialogue and Mission

Secretariate for Non-Christians, “The Attitude of the Church toward the Followers of Other Religions: Reflections and Orientations on Dialogue and Mission”, 1984.

Secretariate for Non-Christians, “The Attitude of the Church toward the Followers of Other Religions: Reflections and Orientations on Dialogue and Mission”, 1984.

Vatican II had set the Church in a new direction, embarking on which many questions had arisen:

- Had dialogue replaced conversion?

- Was mission still necessary?

- What of the Great Commission?

Dialogue and Mission answers these and other questions that had arisen from the praxis and reflection on dialogue over the previous 20 years. It treats the origin and expressions of mission; names the various tasks that make up the contemporary Church’s mission; explains the foundations and forms of dialogue; and treats of the mutual relations between dialogue and mission.

Unfortunately, both the title and structure of the document gave the impression that “dialogue” and “mission” are separate activities. This is contrary to what the text itself states and is an oversight that had to be remedied in the subsequent teaching document.

PCID website: https://www.pcinterreligious.org/pcid-documents

Also available as PDF: Secretariat for Non-Christians. The Attitude of the Church Towards the Followers of Other Religions: Reflections and Orientations on Dialogue and Mission

Supplementary Resources

For supplementary reading on this document see Machado, Felix A. “Dialogue and Mission: A Reading of a Document of the Pontifical Council for Interrreligious Dialogue.” In Milestones in Interreligious Dialogue: A Reading of Selected Catholic Church Documents on Relations with People of Other Religions, edited by Chidi Denis Isizoh, 170-82. Rome, Lagos: Ceedee Publications, 2002.

1990, John Paul II, “Paths of Mission” in Redemptoris Missio

John Paul II, “The Paths of Mission”, in Redemptoris Missio: On the Permanent Validity of the Church’s Missionary Mandate, #41-60

Redemptoris Missio is John Paul II’s missionary encyclical. He affirms the unique role of Christ as the universal Saviour, the centrality of the Kingdom of God and the necessary connections between the Kingdom, Christ and the Church, the role of the Spirit as the principle agent of mission, and the vast horizons of mission.

In Chapter V, “The Paths of Mission” he includes witness (nn. 42-43), proclamation (nn. 44-45), conversion and baptism (nn. 46-47), forming local churches (nn. 48-50), “ecclesial basic communities” (n. 51), incarnating the Gospel in cultures (nn. 52-54), dialogue with our brothers and sisters in other religions (nn. 55-57), promoting development (nn. 58-59), concluding with a reflection on charity as the source and criterion of mission (n. 60).

The remaining chapters of the encyclical deal with personnel for mission, the need for cooperation in mission, and spirituality for mission. The encyclical is an enduring contribution to the theology of mission, and to the role of interreligious dialogue within that mission.

Vatican Website: http://w2.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_07121990_redemptoris-missio.html

Available as a PDF: “Paths of Mission”

For a detailed theological analysis of this text see Dupuis, Jacques. “A Theological Commentary: Dialogue and Proclamation.” In Redemption and Dialogue: Reading Redemptoris Missio and Dialogue and Proclamation, edited by William R Burrows, 119-58. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1993.

1991, PCID and CEP, Dialogue and Proclamation

Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and Congregation for Evangelization of Peoples. Dialogue and Proclamation: Reflections and Orientations on Interreligious Dialogue and the Proclamation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Dialogue and Proclamation is the result of world-wide consultation on five drafts over five year’s collaboration between the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue and the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. Terms are defined and used consistently e.g. the word “proclamation” rather than “mission” or “evangelization” is employed for inviting people to accept Christ and be baptized into the Church. With this distinction, it can now be clearly stated, for the first time, that interreligious dialogue is an integral part of mission.

The document appeals to a scriptural and theological basis for dialogue; acknowledges different forms of dialogue, along with what favors or impedes it. It affirms the mandate of Christ, the role of the Church, its reliance on the Holy Spirit, and the content, urgency, and manner of proclamation. In a final section, the complex relationship between dialogue and proclamation is addressed but not entirely resolved.

Vatican website: http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/interelg/documents/rc_pc_interelg_doc_19051991_dialogue-and-proclamatio_en.html

Available as a PDF: “Dialogue and Proclamation“

With a Preface by Cardinal Jozef Tomko, Prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelisation of Peoples, on the relation of the document, Dialogo y Anuncio, with the encyclical, Redemptoris Missio, from L’OSSERVATORE ROMANO–en lengua española–N. 26 – 28 de junio de 1991 – 16 (376).

For a detailed theological analysis of this text see Dupuis, Jacques. “A Theological Commentary: Dialogue and Proclamation.” In Redemption and Dialogue: Reading Redemptoris Missio and Dialogue and Proclamation, edited by William R Burrows, 119-58. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1993.

1997, ITC, Christianity and the World Religions

International Theological Commission. Christianity and the World Religions.

This document sets the parameters in which Catholic theological reflection on world religions is to take place. It affirms central Catholic doctrines on the role and identity of Christ and the church while retaining an openness to other world religions.

1999, John Paul II, Audience Teachings

In preparation for the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, in his audience teachings of April and May of 1999, Pope John Paul II presented reflections on interreligious dialogue and Nostra Aetate. These included dialogue as part of the Church’s saving mission, relations with Jews, with Muslims, with other world religions, and the Father as humanity’s shared eschatological destination.

In preparation for the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, in his audience teachings of April and May of 1999, Pope John Paul II presented reflections on interreligious dialogue and Nostra Aetate. These included dialogue as part of the Church’s saving mission, relations with Jews, with Muslims, with other world religions, and the Father as humanity’s shared eschatological destination.

2000, CDF, Dominus Iesus

Dominus Iesus is a declaration by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. It affirms traditional Catholic teaching on the role and identity of Jesus Christ as the fullness of revelation and Universal Savior and on the church’s role as the universal mediator of salvation. It refutes any attempt to relativize these positions. The document affirms the positive elements in the sacred writings of other religions (which is attributed to Christ) (par. 8), elements of sanctification and truth outside the Church (which derive their efficacy from the fullness entrusted to the Church) (par. 16), the real possibility of salvation for all humankind (par 20), the encouragement to theologians to explore more fully the mediation of this salvific grace (par. 21), and the confirmation of the exigency for interreligious dialogue (par. 22). While the timing and language of the Declaration proved controversial, any conversation between Catholics and believers from other religions must take into account the authentic teaching on Jesus Christ and the Church which this Declaration sets out.

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Dominus Iesus: On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church.

Available as a PDF: Dominus Iesus

Supplementary Resources

For an introduction to Dominus Iesus read the text of the interview given by Monsignor Bruno Forte of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

Forte, Bruno, 2000. “Dominus Iesus” – Interview. Omnis Terra, no. 311 (2000),

For a detailed evaluation of the positives and negatives of Dominus Iesus read the text of a lecture given by Richard P. McBrien, Crowley-O’Brien-Walter Professor of Theology, University of Notre Dame, USA, given at the Centro Pro Unione on Thursday, 11 January 2001.

McBrien, Richard P. “Dominus Iesus: An Ecclesiological Critique” (2001)

SEDOS website: http://sedosmission.org/old/eng/McBrien.htm

For a more robust criticism of Dominus Iesus see the article by John Prior, an SVD missionary who has spent many years in Indonesia.

Prior, John. “Dominus Iesus” – Or: A Plea for Bold Humility” (2000)

SEDOS website: http://sedosmission.org/old/eng/Prior_2.htm

A literalist reading of the text of paragraph 7 of Dominus Iesus affirms “faith” among Christians but relegates the affirmations of other religions to “beliefs” only. For a nuanced treatment of the proper distinction between faith and belief see McInerney, Patrick “Towards a More Positive Appreciation of the Faith of Muslims: Theological Resolution of Vatican Ambivalence” in Vol. 19, no. 1 of the Australian E-Journal of Theology addresses this issue.

http://aejt.com.au/2012/vol_19/vol_19_no_1_2012/?article=421742

2000, The Great Jubilee

The Great Jubilee

In preparation for and celebration of the Great Jubilee in the Year 2000, Pope John Paul II called for renewal of the church through apostolic letters and apostolic exhortations following continental synods. These addressed the church’s evangelising mission in the context of the new millennium. Naturally, interreligious dialogue was one of the themes treated.

Though references to interreligious dialogue were interspersed throughout the documents, below I have collated those sections which treated the theme in a more focussed way. A thorough study would need to research all the references in these documents, links for which are provided.

Particularly moving was the March 2000 Penitential Rite in St Peter’s Square, in which the Pope and senior curial officials led a Confession of Sins and Asking for Forgiveness. It signalled a humbler, more penitential, honest and open approach by the church towards other peoples, cultures and religions.

Patrick McInerney

List of Jubilee Documents

- Tertio Millennio Adveniente, 10 November 1994, English & Español

- Ecclesia in Africa, 14 September 1995, English & Español

- Ecclesia in Asia, 6 November 1999, English & Español

- International Theological Commission, Memory and Reconciliation: The Church and the Faults of the Past, December 1999, English

- Comisión Teológica Internacional , Memoria y Reconciliación, La Iglesia y las Culpas del Pasado , December 1999, Español

- Day of Pardon, Universal Prayer, Confession of Sins and Asking for Forgiveness, 12 March 2000.

- Ecclesia in Oceania, 22 November 2001, English & Español

- Ecclesia in Europa, 28 June 2003, English & Español

- Novo Millennio Ineunte, 6 January 2001, English & Español

Tertio Millennio Adveniente, 10 November 1994, English

52. Recalling that “Christ … by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and his love, fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear”,(34) two commitments should characterize in a special way the third preparatory year: meeting the challenge of secularism and dialogue with the great religions.

With regard to the former, it will be fitting to broach the vast subject of the crisis of civilization, which has become apparent especially in the West, which is highly developed from the standpoint of technology but is interiorly impoverished by its tendency to forget God or to keep him at a distance. This crisis of civilization must be countered by the civilization of love, founded on the universal values of peace, solidarity, justice and liberty, which find their full attainment in Christ.

53. On the other hand, as far as the field of religious awareness is concerned, the eve of the Year 2000 will provide a great opportunity, especially in view of the events of recent decades, for interreligious dialogue, in accordance with the specific guidelines set down by the Second Vatican Council in its Declaration Nostra Aetate on the relationship of the Church to non-Christian religions.

In this dialogue the Jews and the Muslims ought to have a pre-eminent place. God grant that as a confirmation of these intentions it may also be possible to hold joint meetings in places of significance for the great monotheistic religions.

In this regard, attention is being given to finding ways of arranging historic meetings in places of exceptional symbolic importance like Bethlehem, Jerusalem and Mount Sinai as a means of furthering dialogue with Jews and the followers of Islam, and to arranging similar meetings elsewhere with the leaders of the great world religions. However, care will always have be taken not to cause harmful misunderstandings, avoiding the risk of syncretism and of a facile and deceptive irenicism.

Tertio Millennio Adveniente, 10 November 1994, Español

52. Recordando, además, que « Cristo (…) en la misma revelación del misterio del Padre y de su amor, manifiesta plenamente el hombre al propio hombre y le descubre la sublimidad de su vocación »[34], dos compromisos serán ineludibles especialmente durante el tercer año preparatorio: la confrontación con el secularismo y el diálogo con las grandes religiones.

Respecto al primero, será oportuno afrontar la vasta problemática de la crisis de civilización, que se ha ido manifestando sobre todo en el Occidente tecnológicamente más desarrollado, pero interiormente empobrecido por el olvido y la marginación de Dios. A la crisis de civilización hay que responder con la civilización del amor, fundada sobre valores universales de paz, solidaridad, justicia y libertad, que encuentran en Cristo su plena realización.

53. A su vez, en lo relativo al horizonte de la conciencia religiosa, la vigilia del Dos mil será una gran ocasión, también a la luz de los sucesos de estos últimos decenios, para el diálogo interreligioso, según las claras indicaciones dadas por el Concilio Vaticano II en la Declaración Nostra Aetate sobre las relaciones de la Iglesia con las religiones no cristianas.

En este diálogo deberán tener un puesto preeminente los hebreos y los musulmanes. Quiera Dios que coincidiendo en esta intención se puedan realizar también encuentros comunes en lugares significativos para las grandes religiones monoteístas.

Se estudia, a este respecto, cómo preparar tanto históricas reuniones en Belén, Jerusalén y el Sinaí, lugares de gran valor simbólico, para intensificar el diálogo con los hebreos y los fieles del Islam, como encuentros con los representantes de las grandes religiones del mundo en otras ciudades. Sin embargo, siempre se deberá tener cuidado para no provocar peligrosos malentendidos, vigilando el riesgo del sincretismo y de un fácil y engañoso irenismo.

Ecclesia in Africa, 14 September 1995, English

65. “Openness to dialogue is the Christian’s attitude inside the community as well as with other believers and with men and women of good will”.(107) Dialogue is to be practised first of all within the family of the Church at all levels: between Bishops, Episcopal Conferences or Hierarchical Assemblies and the Apostolic See, between Conferences or Episcopal Assemblies of the different nations of the same continent and those of other continents, and within each particular Church between the Bishop, the presbyterate, consecrated persons, pastoral workers and the lay faithful; and also between different rites within the same Church. SECAM is to establish “structures and means which will ensure the exercise of this dialogue”,(108) especially in order to foster an organic pastoral solidarity.

“United to Jesus Christ by their witness in Africa, Catholics are invited to develop an ecumenical dialogue with all their baptized brothers and sisters of other Christian denominations, in order that the unity for which Christ prayed may be achieved, and in order that their service to the peoples of the Continent may make the Gospel more credible in the eyes of those who are searching for God”.(109) Such dialogue can be conducted through initiatives such as ecumenical translations of the Bible, theological study of various dimensions of the Christian faith or by bearing common evangelical witness to justice, peace and respect for human dignity. For this purpose care will be taken to set up national and diocesan commissions for ecumenism.(110) Together Christians are responsible for the witness to be borne to the Gospel on the Continent. Advances in ecumenism are also aimed at making this witness more effective.

66. “Commitment to dialogue must also embrace all Muslims of good will. Christians cannot forget that many Muslims try to imitate the faith of Abraham and to live the demands of the Decalogue”.(111) In this regard the Message of the Synod emphasizes that the Living God, Creator of heaven and earth and the Lord of history, is the Father of the one great human family to which we all belong. As such, he wants us to bear witness to him through our respect for the values and religious traditions of each person, working together for human progress and development at all levels. Far from wishing to be the one in whose name a person would kill other people, he requires believers to join together in the service of life in justice and peace.(112) Particular care will therefore be taken so that Islamic-Christian dialogue respects on both sides the principle of religious freedom with all that this involves, also including external and public manifestations of faith.(113) Christians and Muslims are called to commit themselves to promoting a dialogue free from the risks of false irenicism or militant fundamentalism, and to raising their voices against unfair policies and practices, as well as against the lack of reciprocity in matters of religious freedom.(114)

67. With regard to African traditional religion, a serene and prudent dialogue will be able, on the one hand, to protect Catholics from negative influences which condition the way of life of many of them and, on the other hand, to foster the assimilation of positive values such as belief in a Supreme Being who is Eternal, Creator, Provident and Just Judge, values which are readily harmonized with the content of the faith. They can even be seen as a preparation for the Gospel, because they contain precious semina Verbi which can lead, as already happened in the past, a great number of people “to be open to the fullness of Revelation in Jesus Christ through the proclamation of the Gospel”.(115)

The adherents of African traditional religion should therefore be treated with great respect and esteem, and all inaccurate and disrespectful language should be avoided. For this purpose, suitable courses in African traditional religion should be given in houses of formation for priests and religious.(116)

Ecclesia in Africa, 14 September 1995, Español

Diálogo

65. « La actitud de diálogo es el modo de ser del cristiano tanto dentro de su comunidad, como en relación con los demás creyentes y con los hombres y mujeres de buena voluntad »[107]. El diálogo se ha de practicar ante todo dentro de la Iglesia- Familia, a todos los niveles: entre Obispos, Conferencias Episcopales o Asambleas de la Jerarquía y Sede Apostólica, entre las Conferencias o Asambleas Episcopales de las diferentes naciones del mismo continente y las de los demás continentes y, en cada Iglesia particular, entre el Obispo, presbiterio, personas consagradas, agentes pastorales y fieles laicos; así como entre los diversos ritos dentro de la misma Iglesia. El S.C.E.A.M. procurará tener « estructuras y medios que garanticen el ejercicio de este diálogo »[108], en particular para favorecer una solidaridad pastoral orgánica.

« Los católicos, unidos a Cristo mediante su testimonio en África, están invitados a desarrollar un diálogo ecuménico con todos los hermanos bautizados de las demás Confesiones cristianas, a fin de lograr la unidad por la que Cristo oró, y de este modo su servicio a las poblaciones del continente haga el Evangelio más creíble a los ojos de cuantos y cuantas buscan a Dios »[109]. Este diálogo podrá concretarse en iniciativas como la traducción ecuménica de la Biblia, la profundización teológica de uno u otro aspecto de la fe cristiana, o incluso ofreciendo juntos un testimonio evangélico a favor de la justicia, la paz y el respeto de la dignidad humana. Para esto se procurará crear comisiones nacionales y diocesanas de ecumenismo[110]. Juntos, los cristianos son responsables de dar testimonio del Evangelio en el continente. Los progresos del ecumenismo tienen también como objetivo hacer que este testimonio sea más eficaz.

66. « El compromiso del diálogo debe abarcar también a los musulmanes de buena voluntad. Los cristianos no pueden olvidar que muchos musulmanes tratan de imitar la fe de Abraham y vivir las exigencias del Decálogo »[111]. A este respecto, el Mensaje del Sínodo destaca que el Dios vivo, Creador del cielo y de la tierra y Señor de la historia, es el Padre de la gran familia humana que formamos. Como tal, quiere que demos testimonio de Él respetando los valores y las tradiciones religiosas propias de cada uno, trabajando juntos para la promoción humana y el desarrollo en todos los niveles. Lejos de querer ser aquél en cuyo nombre unos eliminan a otras personas, Él compromete a los creyentes a trabajar juntos al servicio de la justicia y la paz[112]. Se pondrá, pues, particular atención en que el diálogo islamo-cristiano respete por ambas partes el ejercicio de la libertad religiosa, con todo lo que esto comporta, incluidas también las manifestaciones exteriores y públicas de la fe[113]. Cristianos y musulmanes están llamados a comprometerse en la promoción de un diálogo inmune de los riesgos derivados de un irenismo de mala ley o de un fundamentalismo militante, y levantando su voz contra políticas y prácticas desleales, así como contra toda falta de reciprocidad en relación con la libertad religiosa[114].

67. En cuanto a la religión tradicional africana, un diálogo sereno y prudente podrá, por una parte, proteger de influjos negativos que condicionan la misma forma de vida de muchos católicos y, por otra, asegurar la asimilación de los valores positivos como la creencia en el Ser Supremo, Eterno, Creador, Providente y justo Juez que se armonizan bien con el contenido de la fe. Éstos pueden ser vistos como una preparación al Evangelio, porque contienen preciosas semina Verbi capaces de llevar, como ya ha ocurrido en el pasado, a muchas personas a « abrirse a la plenitud de la Revelación en Jesucristo por medio de la proclamación del Evangelio »[115].

Por tanto, es necesario tratar con mucho respeto y estima a quienes se adhieren a la religión tradicional, evitando todo lenguaje inadecuado e irrespetuoso. A este fin, en los centros de formación sacerdotal y religiosa se deben impartir oportunos conocimientos sobre la religión tradicional[116].

Ecclesia in Asia, 6 November 1999, English

A Mission of Dialogue

29. The common theme of the various “continental” Synods which have helped to prepare the Church for the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000 is that of the new evangelization. A new era of proclamation of the Gospel is essential not only because, after two millennia, a major part of the human family still does not acknowledge Christ, but also because the situation in which the Church and the world find themselves at the threshold of the new millennium is particularly challenging for religious belief and the moral truths which spring from it. There is a tendency almost everywhere to build progress and prosperity without reference to God, and to reduce the religious dimension of the human person to the private sphere. Society, separated from the most basic truth about man, namely his relationship to the Creator and to the redemption brought about by Christ in the Holy Spirit, can only stray further and further from the true sources of life, love and happiness. This violent century which is fast coming to a close bears terrifying witness to what can happen when truth and goodness are abandoned in favour of the lust for power and self-aggrandizement. The new evangelization, as a call to conversion, grace and wisdom, is the only genuine hope for a better world and a brighter future. The question is not whether the Church has something essential to say to the men and women of our time, but how she can say it clearly and convincingly!

At the time of the Second Vatican Council, my predecessor Pope Paul VI declared, in his Encyclical Letter Ecclesiam Suam, that the question of the relationship between the Church and the modern world was one of the most important concerns of our time. He wrote that “its existence and its urgency are such as to create a burden on our soul, a stimulus, a vocation”. 147 Since the Council the Church has consistently shown that she wants to pursue that relationship in a spirit of dialogue. The desire for dialogue, however, is not simply a strategy for peaceful coexistence among peoples; it is an essential part of the Church’s mission because it has its origin in the Father’s loving dialogue of salvation with humanity through the Son in the power of the Holy Spirit. The Church can accomplish her mission only in a way that corresponds to the way in which God acted in Jesus Christ: he became man, shared our human life and spoke in a human language to communicate his saving message. The dialogue which the Church proposes is grounded in the logic of the Incarnation. Therefore, nothing but fervent and unselfish solidarity prompts the Church’s dialogue with the men and women of Asia who seek the truth in love.

As the sacrament of the unity of all mankind, the Church cannot but enter into dialogue with all peoples, in every time and place. Responding to the mission she has received, she ventures forth to meet the peoples of the world, conscious of being a “little flock” within the vast throng of humanity (cf. Lk 12:32), but also of being leaven in the dough of the world (cf. Mt 13:33). Her efforts to engage in dialogue are directed in the first place to those who share her belief in Jesus Christ the Lord and Saviour. It extends beyond the Christian world to the followers of every other religious tradition, on the basis of the religious yearnings found in every human heart. Ecumenical dialogue and interreligious dialogue constitute a veritable vocation for the Church.

Ecumenical Dialogue

30. Ecumenical dialogue is a challenge and a call to conversion for the whole Church, especially for the Church in Asia where people expect from Christians a clearer sign of unity. For all peoples to come together in the grace of God, communion needs to be restored among those who in faith have accepted Jesus Christ as Lord. Jesus himself prayed and does not cease to call for the visible unity of his disciples, so that the world may believe that the Father has sent him (cf. Jn 17:21). 148 But the Lord’s will that his Church be one awaits a complete and courageous response from his disciples.

In Asia, precisely where the number of Christians is proportionately small, division makes missionary work still more difficult. The Synod Fathers acknowledged that “the scandal of a divided Christianity is a great obstacle for evangelization in Asia”. 149 In fact, the division among Christians is seen as a counter-witness to Jesus Christ by many in Asia who are searching for harmony and unity through their own religions and cultures. Therefore the Catholic Church in Asia feels especially impelled to work for unity with other Christians, realizing that the search for full communion demands from everyone charity, discernment, courage and hope. “In order to be authentic and bear fruit, ecumenism requires certain fundamental dispositions on the part of the Catholic faithful: in the first place, charity that shows itself in goodness and a lively desire to cooperate wherever possible with the faithful of other Churches and Ecclesial Communities; secondly, fidelity towards the Catholic Church, without however ignoring or denying the shortcomings manifested by some of her members; thirdly, a spirit of discernment in order to appreciate all that is good and worthy of praise. Finally, a sincere desire for purification and renewal is also needed”. 150

While recognizing the difficulties still existing in the relationships between Christians, which involve not only prejudices inherited from the past but also judgments rooted in profound convictions which involve conscience, 151 the Synod Fathers also pointed to signs of improved relations among some Christian Churches and Ecclesial Communities in Asia. Catholic and Orthodox Christians, for example, often recognize a cultural unity with one another, a sense of sharing important elements of a common ecclesial tradition. This forms a solid basis for a continuing fruitful ecumenical dialogue into the next millennium, which, we must hope and pray, will ultimately bring an end to the divisions of the millennium that is now coming to a close.

On the practical level, the Synod proposed that the national Episcopal Conferences in Asia invite other Christian Churches to join in a process of prayer and consultation in order to explore the possibilities of new ecumenical structures and associations to promote Christian unity. The Synod’s suggestion that the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity be celebrated more fruitfully is also helpful. Bishops are encouraged to set up and oversee ecumenical centres of prayer and dialogue; and adequate formation for ecumenical dialogue needs to be included in the curriculum of seminaries, houses of formation and educational institutions.

Interreligious Dialogue

31. In my Apostolic Letter Tertio Millennio Adveniente I indicated that the advent of a new millennium offers a great opportunity for interreligious dialogue and for meetings with the leaders of the great world religions. 152 Contact, dialogue and cooperation with the followers of other religions is a task which the Second Vatican Council bequeathed to the whole Church as a duty and a challenge. The principles of this search for a positive relationship with other religious traditions are set out in the Council’s Declaration Nostra Aetate, promulgated on 28 October 1965, the Magna Carta of interreligious dialogue for our times. From the Christian point of view, interreligious dialogue is more than a way of fostering mutual knowledge and enrichment; it is a part of the Church’s evangelizing mission, an expression of the mission ad gentes. 153 Christians bring to interreligious dialogue the firm belief that the fullness of salvation comes from Christ alone and that the Church community to which they belong is the ordinary means of salvation. 154 Here I repeat what I wrote to the Fifth Plenary Assembly of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences: “Although the Church gladly acknowledges whatever is true and holy in the religious traditions of Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam as a reflection of that truth which enlightens all people, this does not lessen her duty and resolve to proclaim without failing Jesus Christ who is ‘the way and the truth and the life’… The fact that the followers of other religions can receive God’s grace and be saved by Christ apart from the ordinary means which he has established does not thereby cancel the call to faith and baptism which God wills for all people”. 155

In the process of dialogue, as I have already written in my Encyclical Letter Redemptoris Missio, “there must be no abandonment of principles nor false irenicism, but instead a witness given and received for mutual advancement on the road of religious inquiry and experience, and at the same time for the elimination of prejudice, intolerance and misunderstandings”. 156 Only those with a mature and convinced Christian faith are qualified to engage in genuine interreligious dialogue. “Only Christians who are deeply immersed in the mystery of Christ and who are happy in their faith community can without undue risk and with hope of positive fruit engage in interreligious dialogue”. 157 It is therefore important for the Church in Asia to provide suitable models of interreligious dialogue—evangelization in dialogue and dialogue for evangelization—and suitable training for those involved.

Having stressed the need in interreligious dialogue for firm faith in Christ, the Synod Fathers went on to speak of the need for a dialogue of life and heart. The followers of Christ must have the gentle and humble heart of their Master, never proud, never condescending, as they meet their partners in dialogue (cf. Mt 11:29). “Interreligious relations are best developed in a context of openness to other believers, a willingness to listen and the desire to respect and understand others in their differences. For all this, love of others is indispensable. This should result in collaboration, harmony and mutual enrichment”. 158

To guide those engaged in the process, the Synod suggested that a directory on interreligious dialogue be drawn up. 159 As the Church explores new ways of encountering other religions, I mention some forms of dialogue already taking place with good results, including scholarly exchanges between experts in the various religious traditions or representatives of those traditions, common action for integral human development and the defence of human and religious values. 160 I repeat how important it is to revitalize prayer and contemplation in the process of dialogue. Men and women in the consecrated life can contribute very significantly to interreligious dialogue by witnessing to the vitality of the great Christian traditions of asceticism and mysticism. 161

The memorable meeting held in Assisi, the city of Saint Francis, on 27 October 1986, between the Catholic Church and representatives of the other world religions shows that religious men and women, without abandoning their own traditions, can still commit themselves to praying and working for peace and the good of humanity. 162 The Church must continue to strive to preserve and foster at all levels this spirit of encounter and cooperation between religions.

Communion and dialogue are two essential aspects of the Church’s mission, which have their infinitely transcendent exemplar in the mystery of the Trinity, from whom all mission comes and to whom it must be directed. One of the great “birthday” gifts which the members of the Church, and especially her Pastors, can offer the Lord of History on the two thousandth anniversary of his Incarnation is a strengthening of the spirit of unity and communion at every level of ecclesial life, a renewed “holy pride” in the Church’s continuing fidelity to what has been handed down, and a new confidence in the unchanging grace and mission which sends her out among the peoples of the world to witness to God’s saving love and mercy. Only if the People of God recognize the gift that is theirs in Christ will they be able to communicate that gift to others through proclamation and dialogue.

Ecclesia in Asia, 6 November 1999, Español

Una misión de diálogo

29. El tema común de varios Sínodos «continentales», que han contribuido a la preparación de la Iglesia para el gran jubileo del año 2000, es el de la nueva evangelización. Una nueva época de anuncio del Evangelio es esencial no sólo porque, después de dos mil años, gran parte de la familia humana aún no reconoce a Cristo, sino también porque la situación en que la Iglesia y el mundo se encuentran, en el umbral del nuevo milenio, plantea particulares desafíos a la fe religiosa y a las verdades morales que derivan de ella. Existe una tendencia casi generalizada a construir el progreso y la prosperidad sin referencias a Dios, y a reducir la dimensión religiosa de la persona a la esfera privada. La sociedad, separada de las verdades más fundamentales que atañen al hombre, y específicamente su relación con el Creador y con la redención realizada por Cristo en el Espíritu Santo, sólo puede perder cada vez más las verdaderas fuentes de la vida, el amor y la felicidad. Este siglo violento, que está a punto de llegar a su fin, da un terrible testimonio de lo que puede suceder cuando se abandonan la verdad y la bondad por el afán de poder y por la afirmación de sí mismos en perjuicio de los demás. La nueva evangelización, como invitación a la conversión, a la gracia y a la sabiduría, es la única esperanza auténtica para un mundo mejor y para un futuro más luminoso. La cuestión no consiste en si la Iglesia tiene algo esencial que decir a los hombres y mujeres de nuestro tiempo, sino más bien si lo puede decir con claridad y de modo convincente.

Durante el concilio Vaticano II, mi predecesor el Papa Pablo VI declaró, en la carta encíclica Ecclesiam suam, que la cuestión de la relación entre la Iglesia y el mundo moderno era una de las preocupaciones más importantes de nuestro tiempo, y escribió que «su presencia y su urgencia son tales, que constituyen un peso en nuestro espíritu, un estímulo, casi una vocación»[147]. Desde el Concilio hasta hoy, la Iglesia ha demostrado con coherencia que quiere entablar esa relación con espíritu de diálogo. Sin embargo, el deseo de diálogo no es simplemente una estrategia para una coexistencia pacífica entre los pueblos; más bien, es parte esencial de la misión de la Iglesia, ya que hunde sus raíces en el diálogo amoroso de salvación que el Padre mantiene con la humanidad, en el Hijo, con la fuerza del Espíritu Santo. La Iglesia sólo puede cumplir su misión de un modo que corresponda a la manera en que Dios actuó en Jesucristo, que se hizo hombre, compartió la vida humana y habló un lenguaje humano para comunicar su mensaje salvífico. Este diálogo que la Iglesia propone se funda en la lógica de la Encarnación. Por tanto, solamente una auténtica y desinteresada solidaridad impulsa a la Iglesia al diálogo con los hombres y mujeres de Asia que buscan la verdad en el amor.

La Iglesia, sacramento de la unidad del género humano, no puede por menos de entrar en diálogo con todos los pueblos, en todos los tiempos y lugares. Por la misión que ha recibido, sale al encuentro de los pueblos del mundo, convencida de que es «un pequeño rebaño» dentro de la inmensa multitud de la humanidad (cf. Lc 12, 32), pero también de que es levadura en la masa del mundo (cf. Mt 13, 33). Los esfuerzos por comprometerse en el diálogo se dirigen ante todo hacia quienes comparten la fe en Jesucristo, Señor y Salvador, y luego se extienden, más allá del mundo cristiano, hasta los seguidores de las demás tradiciones religiosas, sobre la base del anhelo religioso presente en todo corazón humano. Así pues, el diálogo ecuménico y el interreligioso constituyen para la Iglesia una auténtica vocación.

El diálogo ecuménico

30. El diálogo ecuménico es un desafío y una llamada a la conversión para toda la Iglesia, especialmente para la Iglesia en Asia, donde los habitantes esperan que los cristianos den un signo más claro de unidad. Es preciso restablecer la comunión entre los que con fe han aceptado a Jesucristo como Señor, para que todos los pueblos puedan reunirse por la gracia de Dios. Jesús mismo oró por la unidad visible de sus discípulos y no deja de estimularlos a ella, para que el mundo crea que el Padre lo envió (cf. Jn 17, 21)[148]. Pero la voluntad del Señor de que su Iglesia sea una, exige una respuesta completa y valiente de sus discípulos.

En Asia, precisamente donde el número de los cristianos es proporcionalmente escaso, la división hace que la actividad misionera resulte aún más difícil. Los padres sinodales constataron que «el escándalo de una cristiandad dividida es un gran obstáculo para la evangelización en Asia»[149]. En efecto, los que en Asia buscan la armonía y la unidad a través de sus religiones y culturas consideran la división entre los cristianos como un antitestimonio de Jesucristo. Por eso, la Iglesia católica en Asia se siente particularmente impulsada a promover la unidad con los demás cristianos, consciente de que la búsqueda de la comunión plena requiere de cada uno caridad, discernimiento, valentía y esperanza. «El ecumenismo, para ser auténtico y fecundo, exige, además, por parte de los fieles católicos, algunas disposiciones fundamentales. Ante todo, la caridad, con una mirada llena de simpatía y un vivo deseo de cooperar, donde sea posible, con los hermanos de las demás Iglesias o comunidades eclesiales. En segundo lugar, la fidelidad a la Iglesia católica, sin desconocer ni negar las faltas manifestadas por el comportamiento de algunos de sus miembros. En tercer lugar, el espíritu de discernimiento, para apreciar lo que es bueno y digno de elogio. Por último, se requiere una sincera voluntad de purificación y renovación»[150].

Los padres sinodales, aunque reconocieron las dificultades que todavía existen en las relaciones entre los cristianos, que implican no sólo prejuicios heredados del pasado sino también creencias arraigadas en profundas convicciones que afectan a la conciencia[151], pusieron de relieve los signos de la mejoría de las relaciones entre algunas Iglesias y comunidades cristianas en Asia. Por ejemplo, católicos y ortodoxos reconocen a menudo una unidad cultural entre ellos, un sentido de participación de elementos importantes de una tradición eclesial común. Esto constituye una sólida base para un diálogo ecuménico fructuoso que pueda proseguir también en el próximo milenio, y que —como esperamos y pedimos a Dios— al final ponga fin a las divisiones del milenio que está a punto de concluir.

En el ámbito práctico, el Sínodo propuso que las Conferencias episcopales de Asia inviten a las demás Iglesias cristianas a unirse en un camino de oración y consultas para crear nuevos organismos y asociaciones ecuménicos con vistas a la promoción de la unidad de los cristianos. Ayudará también la sugerencia del Sínodo de que la Semana de oración por la unidad de los cristianos se celebre con más provecho. Es conveniente que los obispos instituyan y presidan centros ecuménicos de oración y diálogo; asimismo, es necesario incluir en el currículo de los seminarios, de las casas de formación y de las instituciones educativas, una formación adecuada con vistas al diálogo ecuménico.

El diálogo interreligioso

31. En la carta apostólica Tertio millennio adveniente indiqué que la cercanía de un nuevo milenio brinda una gran oportunidad para el diálogo interreligioso y para encuentros con los líderes de las grandes religiones del mundo[152]. El concilio Vaticano II encomendó a toda la Iglesia, como un deber y un desafío, la tarea de llevar a cabo los contactos, el diálogo y la cooperación con los seguidores de las demás religiones. Los principios para la búsqueda de una relación positiva con las demás tradiciones religiosas se hallan enunciados en la declaración conciliar Nostra aetate, promulgada el 28 de octubre de 1965. Es la carta magna del diálogo interreligioso para nuestros tiempos. Desde el punto de vista cristiano, el diálogo interreligioso es mucho más que un modo de promover el conocimiento y el enriquecimiento recíprocos; es parte de la misión evangelizadora de la Iglesia, una expresión de la misión ad gentes[153]. Los cristianos aportan a este diálogo la firme convicción de que la plenitud de la salvación proviene sólo de Cristo y que la comunidad de la Iglesia a la que pertenecen es el medio ordinario de salvación[154]. Repito aquí lo que escribí a la V Asamblea plenaria de la Federación de las Conferencias episcopales de Asia: «Aunque la Iglesia reconoce con gusto cuanto hay de verdadero y santo en las tradiciones religiosas del budismo, el hinduismo y el islam, reflejos de la verdad que ilumina a todos los hombres, sigue en pie su deber y su determinación de proclamar sin titubeos a Jesucristo, que es isel camino, la verdad y la vidald (Jn 14, 6; cf. Nostra aetate, 2). (…) El hecho de que los seguidores de otras religiones puedan recibir la gracia de Dios y ser salvados por Cristo independientemente de los medios ordinarios que él ha establecido, no anula la llamada a la fe y al bautismo, que Dios quiere para todos los pueblos»[155].

Con respecto al proceso del diálogo, en la carta encíclica Redemptoris missio escribí: «No debe darse ningún tipo de abdicación ni de irenismo, sino el testimonio recíproco para un progreso común en el camino de búsqueda y experiencia religiosa y, al mismo tiempo, para superar prejuicios, intolerancias y malentendidos»[156]. Sólo quienes poseen una fe cristiana madura y convencida están preparados para participar en un auténtico diálogo interreligioso. «Únicamente los cristianos profundamente inmersos en el misterio de Cristo y felices en su comunidad de fe pueden, sin riesgo inútil y con esperanza de frutos positivos, participar en el diálogo interreligioso»[157]. Por eso, es importante que la Iglesia en Asia proporcione modelos correctos de diálogo interreligioso (evangelización en el diálogo y diálogo para la evangelización) y una preparación adecuada para los que están implicados en él.

Después de subrayar la necesidad de una sólida fe en Cristo con vistas al diálogo interreligioso, los padres sinodales hablaron de la necesidad de un diálogo de vida y de corazón. Los seguidores de Cristo deben tener un corazón humilde y cordial como el del Maestro, nunca soberbio ni condescendiente, cuando participan en el diálogo con los demás (cf. Mt 11, 29). «Las relaciones interreligiosas se desarrollan mucho mejor en un marco de apertura a otros creyentes, voluntad de escucha y deseo de respetar y comprender a los demás en sus diferencias. Por eso, es indispensable el amor a los demás. Eso debería llevar a la colaboración, a la armonía y al enriquecimiento mutuo[158].

Para orientar a los que están comprometidos en ese proceso, el Sínodo sugirió que se elabore un directorio para el diálogo interreligioso[159]. Mientras la Iglesia busca nuevos caminos de encuentro con otras religiones, deseo recordar algunas formas de diálogo que ya están dando buenos resultados: los intercambios académicos entre expertos en las diversas tradiciones religiosas o representantes de éstas, la acción común en favor del desarrollo humano integral y la defensa de los valores humanos y religiosos[160]. Deseo reafirmar la importancia que tiene, en el proceso del diálogo, revitalizar la oración y la contemplación. Las personas de vida consagrada pueden contribuir de modo significativo al diálogo interreligioso, testimoniando la vitalidad de las grandes tradiciones cristianas de ascetismo y misticismo[161].

El memorable encuentro de Asís, ciudad de san Francisco, el 27 de octubre de 1986, entre la Iglesia católica y los representantes de las demás religiones mundiales demuestra que los hombres y mujeres de religión, sin abandonar sus respectivas tradiciones, pueden comprometerse en la oración y trabajar por la paz y el bien de la humanidad[162]. La Iglesia debe seguir esforzándose por preservar y promover en todos los niveles este espíritu de encuentro y colaboración con las demás religiones.

La comunión y el diálogo son dos aspectos esenciales de la misión de la Iglesia: tienen su modelo infinitamente trascendente en el misterio de la Trinidad, de la que procede toda misión y a la que debe volver. Uno de los grandes dones «de cumpleaños» que los miembros de la Iglesia, especialmente los pastores, pueden ofrecer al Señor de la historia en el 2000° aniversario de la Encarnación es el fortalecimiento del espíritu de unidad y comunión en todos los niveles de la vida eclesial, un «santo orgullo» en la fidelidad constante de la Iglesia a lo que ha recibido, una nueva confianza en la gracia y en la misión perennes que la envían entre los pueblos del mundo como testigo del amor y de la misericordia salvíficos de Dios. Sólo si el pueblo de Dios reconoce el don que ha recibido en Cristo, será capaz de comunicarlo a los demás mediante el anuncio y el diálogo.

International Theological Commission, Memory and Reconciliation: The Church and the Faults of the Past, December 1999, English

6.3 The Implications for Dialogue and Mission

On the level of dialogue and mission, the foreseeable implications of the Church’s acknowledgement of past faults are varied.

On the level of the Church’s missionary effort, it is important that these acts do not contribute to a lessening of zeal for evangelization by exacerbating negative aspects. At the same time, it should be noted that such acts can increase the credibility of the Christian message, since they stem from obedience to the truth and tend to produce fruits of reconciliation. In particular, with regard to the precise topics of such acts, those involved in the Church’s mission ad gentes should take careful account of the local context in proposing these, in light of the capacity of people to receive such acts (thus, for example, aspects of the history of the Church in Europe may well turn out to have little significance for many non-European peoples).

With respect to ecumenism, the purpose of ecclesial acts of repentance can be none other than the unity desired by the Lord. Therefore, it is hoped that they will be carried out reciprocally, though at times prophetic gestures may call for a unilateral and absolutely gratuitous initiative.

On the inter-religious level, it is appropriate to point out that, for believers in Christ, the Church’s recognition of past wrongs is consistent with the requirements of fidelity to the Gospel, and therefore constitutes a shining witness of faith in the truth and mercy of God as revealed by Jesus. What must be avoided is that these acts be mistaken as confirmation of possible prejudices against Christianity. It would also be desirable if these acts of repentance would stimulate the members of other religions to acknowledge the faults of their own past. Just as the history of humanity is full of violence, genocide, violations of human rights and the rights of peoples, exploitation of the weak and glorification of the powerful, so too the history of the various religions is marked by intolerance, superstition, complicity with unjust powers, and the denial of the dignity and freedom of conscience. Christians have been no exception and are aware that all are sinners before God!

In the dialogue with cultures, one must, above all, keep in mind the complexity and plurality of the notions of repentance and forgiveness in the minds of those with whom we dialogue. In every case, the Church’s taking responsibility for past faults should be explained in the light of the Gospel and of the presentation of the crucified Lord, who is the revelation of mercy and the source of forgiveness, in addition to explaining the nature of ecclesial communion as a unity through time and space. In the case of a culture that is completely alien to the idea of seeking forgiveness, the theological and spiritual reasons which motivate such an act should be presented in appropriate fashion, beginning with the Christian message and taking into account its critical-prophetic character. Where one may be dealing with a prejudicial indifference to the language of faith, one should take into account the possible double effect of an act of repentance by the Church: on the one hand, negative prejudices or disdainful and hostile attitudes might be confirmed; on the other hand, these acts share in the mysterious attraction exercised by the “crucified God.”(97) One should also take into account the fact that in the current cultural context, above all of the West, the invitation to a purification of memory involves believers and non-believers alike in a common commitment. This common effort is itself already a positive witness of docility to the truth.

Lastly, in relation to civil society, consideration must be given to the difference between the Church as a mystery of grace and every human society in time. Emphasis must also be given, however, to the character of exemplarity of the Church’s requests for forgiveness, as well as to the consequent stimulus this may offer for undertaking similar steps for purification of memory and reconciliation in other situations where it might be urgent. John Paul II states: “The request for forgiveness…primarily concerns the life of the Church, her mission of proclaiming salvation, her witness to Christ, her commitment to unity, in a word, the consistency which should distinguish Christian life. But the light and strength of the Gospel, by which the Church lives, also have the capacity, in a certain sense, to overflow as illumination and support for the decisions and actions of civil society, with full respect for their autonomy… On the threshold of the third millennium, we may rightly hope that political leaders and peoples, especially those involved in tragic conflicts fuelled by hatred and the memory of often ancient wounds, will be guided by the spirit of forgiveness and reconciliation exemplified by the Church and will make every effort to resolve their differences through open and honest dialogue.”(98)

Comisión Teológica Internacional , Memoria y Reconciliación, La Iglesia y las Culpas del Pasado , December 1999, Español

6.3 Las implicaciones en el plano del diálogo y de la misión

Las implicaciones previsibles en el plano del diálogo y de la misión, como consecuencia de un reconocimiento eclesial de las culpas del pasado, son diversas:

a) En el plano misionero hay que evitar, ante todo, que tales actos contribuyan a disminuir el impulso de la evangelización mediante la exasperación de los aspectos negativos. No obstante, se debe tener en cuenta el hecho de que estos mismos actos podrán hacer crecer la credibilidad del mensaje, en cuanto nacen de la obediencia a la verdad y tienden a frutos efectivos de reconciliación. En particular, los misioneros ad gentes tendrán cuidado en contextualizar la propuesta de estos temas de modo conforme a la efectiva capacidad de recepción en los ambientes en que actúan (por ejemplo, determinados aspectos de la historia de la Iglesia en Europa podrán resultar poco significativos para muchos pueblos no europeos).

b) En el plano ecuménico, la finalidad de posibles actos eclesiales de arrepentimiento no puede ser otra que la unidad querida por el Señor. En esta perspectiva es aún más de desear que sean realizados en reciprocidad, aun cuando a veces gestos proféticos podrán exigir una iniciativa unilateral y absolutamente gratuita.

c) En el plano interreligioso es oportuno poner de relieve cómo para los creyentes en Cristo el reconocimiento de las culpas pasadas por parte de la Iglesia es conforme a las exigencias de la fidelidad al Evangelio y, por tanto, constituye un luminoso testimonio de su fe en la verdad y en la misericordia del Dios revelado por Jesús. Lo que hay que evitar es que actos semejantes sean interpretados equivocadamente como confirmaciones de posibles prejuicios respecto al cristianismo. Sería deseable, por otra parte, que estos actos de arrepentimiento estimulasen también a los fieles de otras religiones a reconocer las culpas de su propio pasado. Como la historia de la humanidad está llena de violencias, genocidios, violaciones de los derechos humanos y de los derechos de los pueblos, explotación de los débiles y divinización de los poderosos, del mismo modo la historia de las religiones está revestida de intolerancia, superstición, connivencia con poderes injustos y negación de la dignidad y libertad de las conciencias. ¡Los cristianos no han sido una excepción y son conscientes de cuán pecadores son todos ante Dios!

d) En el diálogo con las culturas se debe tener presente, ante todo, la complejidad y la pluralidad de las mentalidades con que se dialoga, respecto a la idea de arrepentimiento y de perdón. En todos los casos, el hecho de cargar por parte de la Iglesia con las culpas pasadas debe ser iluminado a la luz del mensaje evangélico y, en particular, de la presentación del Señor crucificado, revelación de la misericordia y fuente de perdón, además de la peculiar naturaleza de la comunión eclesial, una en el tiempo y en el espacio. Allí donde una cultura fuese totalmente ajena a la idea de una petición de perdón, deben ser presentadas de modo oportuno las razones teológicas y espirituales que motivan este acto a partir del mensaje cristiano y debe ser tenido en cuenta su carácter crítico-profético. Donde haya que confrontarse con el prejuicio de una actitud de indiferencia hacia la palabra de la fe, se debe tener en cuenta un doble posible efecto de estos actos de arrepentimiento eclesial: si, por una parte, pueden confirmar prejuicios negativos o actitudes de desprecio y de hostilidad, de otra parte participan de la misteriosa atracción característica del «Dios crucificado» 97. Además hay que tener en cuenta el hecho de que, en el actual contexto cultural, sobre todo en Occidente, la invitación a la purificación de la memoria implica un compromiso común a creyentes y no creyentes. Ya este trabajo común constituye un testimonio positivo de docilidad a la verdad.

e) Con relación a la sociedad civil se debe considerar la diferencia que existe entre la Iglesia, misterio de gracia, y cualquier sociedad temporal, pero tampoco se debe olvidar el carácter de ejemplaridad que la petición eclesial de perdón puede presentar y el estímulo consiguiente que puede ofrecer de cara a realizar pasos análogos de purificación de la memoria y de reconciliación en las más diversas situaciones en las que se podría reconocer su urgencia. Afirma Juan Pablo II: «La petición de perdón […] se refiere, en primer lugar, a la vida de la Iglesia, su misión de anunciar la salvación, su testimonio de Cristo, su compromiso por la unidad, en una palabra, la coherencia que debe caracterizar la existencia cristiana. Pero la luz y la fuerza del Evangelio, de que vive la Iglesia, tienen la capacidad de iluminar y sostener, como por sobreabundancia, las opciones y las acciones de la sociedad civil, en el pleno respeto de su autonomía […] En los umbrales del tercer milenio es legítimo esperar que los responsables políticos y los pueblos, sobre todo los que se encuentran inmersos en conflictos dramáticos, alimentados por el odio y por el recuerdo de heridas muchas veces antiguas, se dejen guiar por el espíritu de perdón y de reconciliación testimoniado por la Iglesia y se esfuercen por resolver los contrastes mediante un diálogo leal y abierto» 98.

Day of Pardon, Universal Prayer, Confession of Sins and Asking for Forgiveness, 12 March 2000

http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/documents/ns_lit_doc_20000312_prayer-day-pardon_en.html

http://www.ewtn.com/library/PAPALDOC/JJP2UNPR.HTM (names the representatives of the Curia who read the penitential prayers)

CONFESSION OF SINS AGAINST THE PEOPLE OF ISRAEL

A representative of the Roman Curia:

Let us pray that, in recalling the sufferings

endured by the people of Israel throughout history,

Christians will acknowledge the sins

committed by not a few of their number

against the people of the Covenant and the blessings,

and in this way will purify their hearts.

Silent prayer.

The Holy Father:

God of our fathers,

you chose Abraham and his descendants

to bring your Name to the Nations:

we are deeply saddened by the behaviour of those

who in the course of history

have caused these children of yours to suffer,

and asking your forgiveness we wish to commit ourselves

to genuine brotherhood

with the people of the Covenant.

We ask this through Christ our Lord.

- Amen

- Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie eleison.

A lamp is lit before the Crucifix.

CONFESSION OF SINS COMMITTED IN ACTIONS AGAINST LOVE, PEACE, THE RIGHTS OF PEOPLES, AND RESPECT FOR CULTURES AND RELIGIONS

A representative of the Roman Curia:

Let us pray that contemplating Jesus,

our Lord and our Peace,

Christians will be able to repent of the words and attitudes

caused by pride, by hatred,

by the desire to dominate others,

by enmity towards members of other religions

and towards the weakest groups in society,

such as immigrants and itinerantes

Silent prayer.

The Holy Father:

Lord of the world, Father of all,

through your Son

you asked us to love our enemies,

to do good to those who hate us

and to pray for those who persecute us.

Yet Christians have often denied the Gospel;

yielding to a mentalíty of power,

they have violated the rights of ethnic groups and peoples,

and shown contempt for their cultures and religious traditions:

be patient and merciful towards us, and grant us your forgiveness!

We ask this through Christ our Lord.

- Amen.

- Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison; Kyrie, eleison.

A lamp is lit before the Crucifix.

Ecclesia in Oceania, 22 November 2001, English

Interreligious Dialogue

25. Greater travel opportunities and easier migration have resulted in unprecedented encounters among the cultures of the world, and hence the presence in Oceania of the great non-Christian religions. Some cities have Jewish communities, made up of a considerable number of survivors of the Holocaust, and these communities can play an important role in Jewish-Christian relations. In some places too there are long established Muslim communities; in others, there are communities of Hindus; and in still others, Buddhist centres are being established. It is important that Catholics better understand these religions, their teachings, way of life and worship. Where parents from these religions enrol their children in Catholic schools, the Church has an especially delicate task.

The Church in Oceania also needs to study more thoroughly the traditional religions of the indigenous populations, in order to enter more effectively into the dialogue which Christian proclamation requires. “Proclamation and dialogue are, each in its own place, component elements and authentic forms of the one evangelizing mission of the Church. They are both oriented toward the communication of salvific truth”.(90) In order to pursue a fruitful dialogue with these religions, the Church needs experts in philosophy, anthropology, comparative religions, the social sciences and, above all, theology.

Ecclesia in Oceania, 22 November 2001, Español: