Interreligious Dialogue with Candomble

Interreligious Dialogue with Candomble

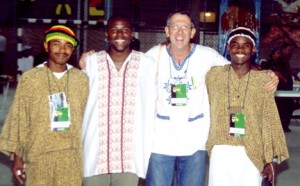

Colin McLean, Brazil

In 1999 I was privileged to be at a history-making meeting of the Black priests, bishops and deacons of Brazil here in the city of Salvador. The meeting is an annual event, but what made this one so special was the presence for the first time of Mae Stella, the most prestigious figure of Candomble in Salvador. Mae Stella who might be described as a priestess or medium declared:

I believe that we are all walking towards the divine along parallel paths, and that one day our paths will converge and we will walk the final distance together.

Candomble is a fascinating and widely-followed Afro-Brazilian religion. Its origins are found in in the tribal Yoruba regions of Nigeria. The connection between Nigeria and Brazil is that during the Atlantic slave traffic Brazil received 40% of the 11 million African slaves shipped across the Atlantic. By contrast, about 6%, or 500,000 of these African slaves were imported into what is now the USA.

The Candomble religion is centered around orixas (pronounced orishas) Yoruba spirits brought across the Atlantic Ocean in the fetid holds of the slave ships. Each of the orixas have divine attributes associated with ecological and cosmological forces, and all human beings have a guardian orixa, whose presence is often gauged from the personality of the individual person.

This was the religion which helped millions of African slaves in Brazil to cope with their servitude and on occasion to resist it. Until the end of the 19th century it was practiced as secret celebrations under cover of night, after finishing a grueling hard days work. In the 1880’s three Nigerian women founded the first official terreiro (sacred space where the orixas could be honoured and invoked) in Salvador. However, Candomble was only legitimized by the government in 1976.

Throughout decades of repression, faith in the Yoruba orixas was channeled into the figures of Catholic saints so as to disguise and preserve it. Hence, spirits with Yoruba-language names such as Xango, Yemanja, Iansa, Oxossi, Oxum and Ogum, were modulated into Catholic saints like St George, the Immaculate Conception, St Barbara, St Sebastian, Our Lady of the Candles, St Anthony etc.

The modern Brazilian government repressed Candomble and other forms of it (which today we call Afro-Brazilian religions) and this was sanctioned by the Catholic Church.

Though Brazilian Catholics in this north-east part of Brazil see Candomble bordering on devil worship, a great number of Catholics would have some belief in, if not fear of, Candomble spirits and practices. These Catholics practice what is called dulpa pertença or “double belonging”.

Increasingly more sensitive to the abominable suffering of African slavery, an ever-growing number of bishops, priests, nuns and lay Catholics today can understand Candomble and can see it as a necessary part of our inter-religious dialogue in Brazil. Fortunately, the various Bishops’ Conferences of Latin America have come to take seriously the cultural and religious experiences of Brazilians of African and Indigenous descent, whose traditions were formerly seen as little more than superstition. One of the major documents from the Aparecida Bishops’ Conference in 2007 states:

To recognize the cultural values, the history and the traditions of afro-americans, to enter into fraternal and respectful dialogue with them, is the first important step in the evangelizing mission of the Church.

I still remember well my first meeting with a Mãe-de-Santo (priestess/medium), Mãe Mildete, back in 1988. The reverence she was accorded by her followers, and her quiet dignity and personal warmth when I was introduced made a deep impression on me. Today, I still feel the quiet dignity that mães-de-santo and pais-de-santo (priest/mediums) seem to possess. The wholehearted participation of the candomblé initiates, the deep reverence for nature in the terreiros (sacred halls where the rituals occur), the warm welcome accorded people visiting the terreiro for the ritual, and the fact that everyone present partakes of food offered after the ritual are things that have impressed me. Candomblé is not a “religion of the book” as are Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It is a oral tradition, and the presence of the orixás in those who go into trances conveys to the congregation that the spirits are still with us today, so all is well. They are good points of entry for dialogue.

Back to Mae Stella whom I mentioned at the beginning. It was so moving to see her seated on the same level between Dom Geraldo Majella Agnelo the Cardinal Archbishop of Salvador, and his auxiliary bishop, Dom Gilio Felicio. He was the first black bishop of Salvador and he was the person responsible for this historic meeting. He made strong efforts towards dialogue with Candomble, visiting all the major Candomble sacred spaces and meeting with the mediums, priestesses and priests. Members Mae Stella’s terreiro, admitted unease about participating for the first time in an official Catholic Church meeting. They were afraid that the term “inter-religious dialogue” might a tactical weapon to win over and control Afro-Brazilian religions.

Although an attempt was made to form an archdiocesan commission for Inter-Religious Dialogue with Candomble in Salvador (of which I was part) it unfortunately floundered. But progress has been made on another front, namely the strong leadership of Fr Clovis Cabral. He is a black Jesuit whose mother, Mae America, was a recognized Mae de Santo, “mother of the saint” – the title given to Candomble mediums who regularly “receive” a particular orixa. All of Fr Cabral’s brothers and sisters (though not himself) have been initiated into Candomble.

A year after Fr Cabral’s mother’s death, I was given the great honour to be invited to participate in a “closed” ritual of commemoration. It took place very late at night and continued until the early hours of the morning. Other more regular Candomble festas that are open to the public do not occur on a weekly basis like Christian liturgies, but are celebrated during a cycle of dates that are considered important to the various orixas or spirits.

The task of entering into dialogue with Candomble or other indigenous religions requires us Catholics to overcome many ingrained prejudices before we can communicate with them at a deep spiritual level.